Source: GenderIT.org

By Subha Wijesiriwardena

“Sexuality could indeed be spoken of, spoken of a great deal, but only in order to forbid it.”

Michel Foucault (as interviewed by Bernard-Henri Lévy in 1977)

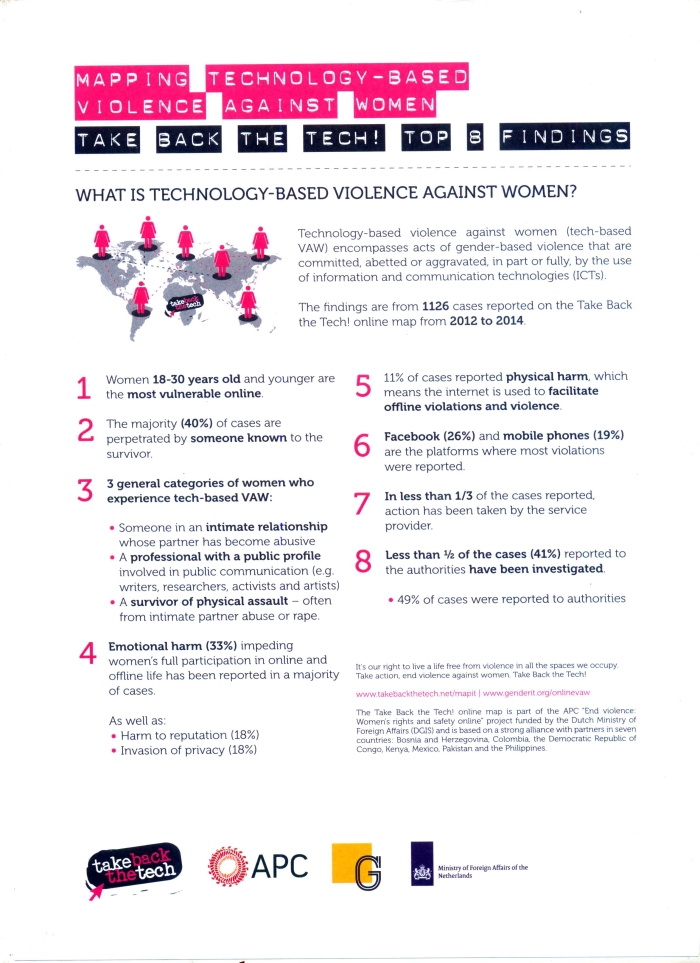

Earlier this year, the telecommunications minister of Bangladesh declared a ‘war on pornography’, blocking access to around 20,000 websites and banning TikTok, the Chinese-owned video production and sharing app. The move came after a petition citing ‘obscenity’ was filed by a civil society organization with the Bangladeshi High Court in November 2018. India followed suit, calling for a ban on TikTok over ‘pornography concerns’ in April this year, though the ban has now been lifted. In Indonesia, TikTok ran into major trouble when the government accused it of disseminating ‘pornographic’ and ‘blasphemous’ content.

But researchers in Sri Lanka have recently pointed to how TikTok is being used as a platform for performance and play by women[1]. Of course, it’s not the first time something that is being instrumentalized in the service of women’s expression, particularly women’s sexual expression, has been black-marked as dangerous and obscene. In fact, this is exactly how it goes.

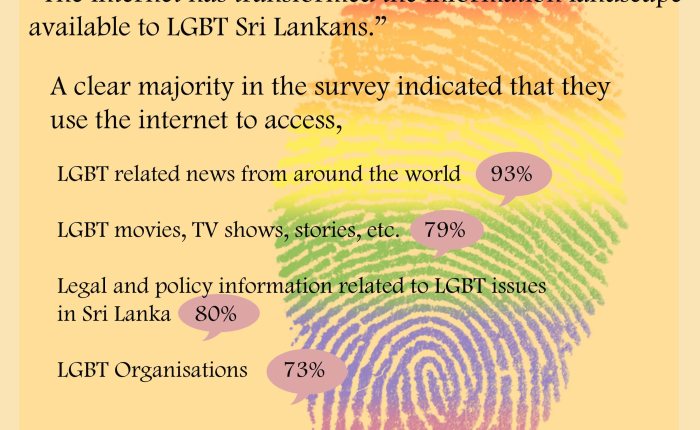

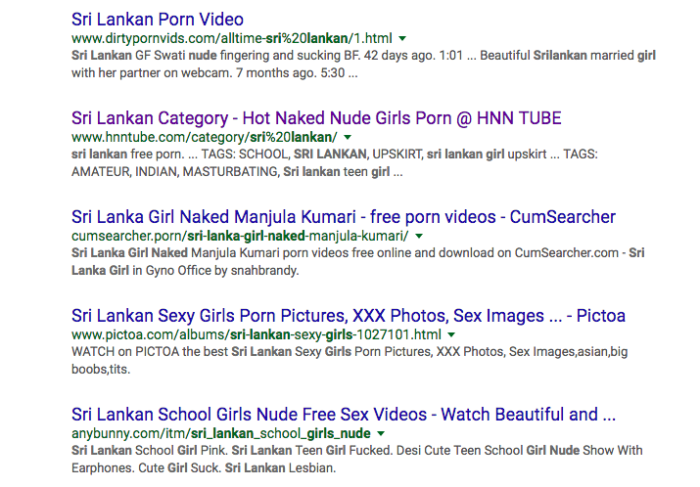

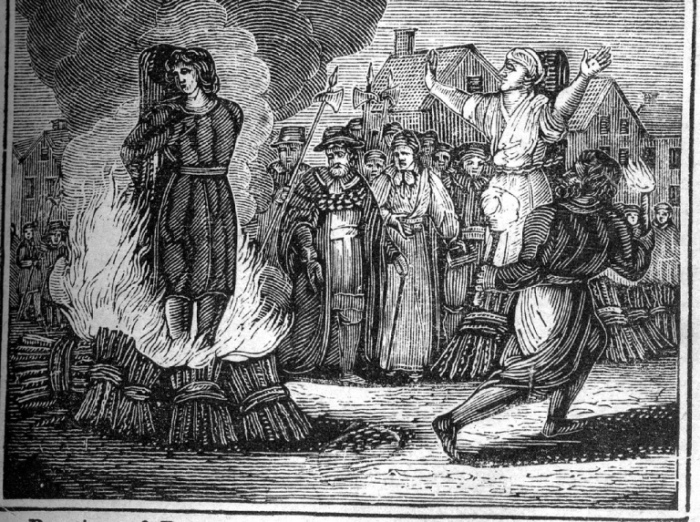

Historically, content which expresses women’s desires or sexualities, or indeed any expression of desire and sexuality considered non-normative, has been first-up on the chopping block, labelled ‘obscene’. And it is not just governments who justify censorship by claiming ‘obscenity’. YouTube is just one of the major internet corporations who have come under fire for the censorship of LGBTQ+ content under restrictions meant to curb content considered pornographic or offensive. Restrictions on such platforms, which are meant to curtail material considered ‘sexual’ and therefore deemed harmful, have categorically been shown to unfairly affect LGBTQ+ content and content by women[2].

Historically, content which expresses women’s desires or sexualities, or indeed any expression of desire and sexuality considered non-normative, has been first-up on the chopping block, labelled ‘obscene’.

The link between anything considered ‘pornography’ and ‘harm’ has been made time and again. Indeed, the debate about pornography has been raging for decades in our own backyard — it remains at the root of a major feminist faultline.

In 1983, in the United States, feminist scholars Catharine Mackinnon and Andrea Dworkin were brought in to draft amendments to the Minneapolis city civil rights ordinance, as a response to growing concern about the city’s adult entertainment district. They wrote an amendment that opponents saw as a de-facto ban, articulating sexually explicit material and its production and sale, as a violation of women’s rights: “the sexually explicit subordination of women, graphically depicted” as “a form of discrimination on the basis of sex.”[3]

It remains at the root of a major feminist faultline

Though the ordinance was struck down and later declared unconstitutional, this heralded the gathering of momentum of an anti-pornography movement.[4] On the other side, ‘sex-positive’ feminists tried to problematize the reductive narratives of ‘violence’, ‘harm’ and ‘exploitation’, claiming anti-pornography arguments authorized a censorial state to prohibit the expression of female sexuality, fundamentally ignored the fact of women’s agency and diminished the political significance of women’s sexual pleasure in a patriarchal world[5]. Largely, feminists still remain divided on how feminists should assess porn and how we understand it.[6]

In India, in a pre-internet era, where the Hindu right-wing and the secular women’s movement agreed on almost nothing, they came together in their fight against ‘obscenity’, when the release of the film Khalanayak (1993) and the film’s most popular song ‘Choli Ke Peeche Kya Hai?’ (translating to ‘What’s behind the blouse?’) caught everyone’s attention[7]. A petition filed at the Delhi High Court which called for the deletion of the song from the film as well as a ban on audio cassette sales, stated the song was ‘vulgar, against public morality and decency’.

Obscenity: a Colonial Legal Framework

The language around ‘obscenity’ forms one of the key legal bases for censorship in many countries; the idea seems to originate from colonial-era laws around obscenity which aimed to criminalize sexual expression and sexuality-related material (which could include sexuality-related educational information) as it was considered ‘harmful’ to society. In many contexts, as we know, colonial criminal law went further, criminalizing aspects of sexual behaviour, even if done in private, deemed ‘unnatural’.[8]

Sexual expression is still widely considered ‘harmful’ to society, with no real proof, but not for a lack of investigation. With pornography, for example, innumerable studies have been done since the 1970s to investigate links between the consumption of pornography and harm. It turns out there is, to date, no conclusive evidence to show that this link can be made. Trying to make a causal link between pornorgraphy and harm has proven problematic not just empirically but methodologically as well, primarily because of a continuing lack of clarity and agreement on what is meant by ‘pornography’ and ‘harm’.[9]

Trying to make a causal link between pornorgraphy and harm has proven problematic not just empirically but methodologically as well

If we want to understand the real reach of these laws — that is to say, their ideological reach — they have to be considered as a sort of whole, a part of the same project, fundamentally underpinned by their shared goals to surveil, regulate and control sexuality, through censorship and criminalization, under the guise of ‘protection’, typically, of women and children. Women and children are still widely considered in need of protection from sexuality, particularly their own.

The State Still Cares

Governments continue to care a great deal about the internet being a medium through which sexual and erotic material can be made and shared. This has become a common justification for state regulation of the internet.

For example, India’s IT Act of 2008 has several clauses pertaining to obscenity and sexual material. Sections 67 and 67A both outlaw the electronic publishing of ‘obscene’ material or any material recording ‘sexual acts’ respectively (with no reference to consent), though Section 66E interestingly explicitly draws on the language of ‘consent’: “If a person captures, transmits or publishes images of a person’s private parts without his/her consent or knowledge…” Richa Kaul Padte writes, “In this respect, section 66E is a progressive clause that places the absence of consent at the heart of criminalising an act.”[10]

However, the principle of consent embedded in this particular provision does not, unfortunately, give us an accurate understanding of the Act as a whole. The Act remains protectionist in its approach at best, and operates on the premise that — as Padte writes — “if female sexuality is the culprit, public morality is the victim”.

As Padte writes — “if female sexuality is the culprit, public morality is the victim”.

Guardians of ‘Free Speech’

Governments of countries like China and Russia have gained notoriety for their sweeping internet censorship policies[11], while other forms of internet regulation, particularly by private actors, are relatively less talked about. As noted before, corporations and governments are seemingly equal partners in a crusade against sexual content. And yet corporations often seem above reproach.

Slowly, the tide may be shifting. Facebook has come under fire in a series of highly publicized Senate hearings in the US, which has led to increased scrutiny and debate about tech corporations responsibilities to users’ rights and human rights more broadly.

But it should come as no surprise that conversations about corporate internet regulation are slow to get airtime. A large part of the regular person’s internet experience is shaped predominantly by about four or five US-based social media platforms, owned more or less by about two or three US-based corporations. It has become almost habit for many of us to point to governments of Global South / non-Western nations as purveyors of censorship, rather than turn to the corporate giants who regulate our internet experiences every minute.

A large part of the regular person’s internet experience is shaped predominantly by about four or five US-based social media platforms, owned more or less by about two or three US-based corporations.

The crackdown on TikTok yields many interesting revelations in this regard: what is the role of geopolitics at play here, where a Chinese-owned app has come under censure for not conforming to the mostly West-determined ideas of what constitutes acceptable content? In addition, it raises the question of class and how class-based morality also finds its way into censorship policies: ‘Tiktok has found particular popularity in smaller cities and towns among first-time internet users who don’t speak English’ says an Indian commentator[12]. Sachini Perera and Minoli Wijetunge in their paper also address class, noting that Sri Lankan women users of TikTok were using the platform to subvert assumptions and ‘shifts norms around women’s sexuality, behaviour and class’.[13]

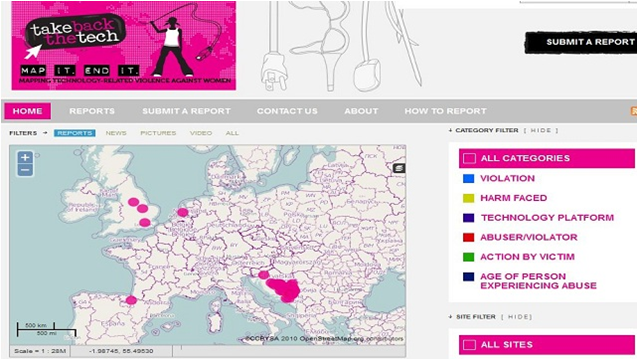

Facebook, Instagram (owned by Facebook), Twitter and YouTube (owned by Google) all have their own user guidelines (used by the thousands of content moderators), which form the bases for content moderation. Though titled things like ‘Community Standards’[14], these guidelines are but frameworks for censorship.

Furthermore, all content moderation, across all platforms, depends on reports from other users. Reporting objectionable content is encouraged. This exercise both cultivates a culture of community surveillance as well as exacts unpaid labour from platform users, a practice which commentators have come to call ‘outsourced content moderation’.

Private Actors, Private Parts

Unsurprisingly, all major platforms have shown great concern over what they consider sexually explicit material. YouTube’s policy states, ‘Explicit content meant to be sexually gratifying (like pornography) is not allowed on YouTube’. The Twitter Rules define adult content (which is disallowed) as ‘any media that is pornographic and/or may be intended to cause sexual arousal’. So, sexual arousal and gratification are unacceptable.

Facebook disallows adult nudity and sexual activity, the ‘sexual exploitation’ of both children and adults which includes but isn’t limited to breaches of consent, and explicitly disallows sexual solicitation between adults. Facebook also elaborately describes what parts of the body (genitalia, buttocks etc.) it considers sexually explicit by default. Though many of these policies seem to draw from the logic of the colonial arguments of ‘obscenity’, their language is deliberately different. But it’s important to remember that they are effectively setting out to perform the same function as those colonial-era laws, in the digital age.

These online platforms are effectively setting out to perform the same function as those colonial-era laws, in the digital age.

All major platforms have come under some scrutiny in relation to how these policies are affecting the lives of real people. The Free the Nipple campaign and its social media incarnation shone a light on the hypocrisy and sexism embedded in the blanket censure hich women’s breasts online. But if the changes in some of the social media policies on nudity are a reflection of the nipple debate, then we can conclude that even when breasts emerged victorious in the struggle, they were only acceptable in non-sexual contexts[15]. Who’s fighting for our right to bear our breasts, with all their sexual connotations?

Instagram came under considerable scrutiny after it took down a series of photographs shared by now popular poet Rupi Kaur, the first of which showed her sleeping in pants stained by menstrual blood. These images did not, in effect, violate its policy on nudity at all. This was just one illustration of how women’s bodies, in general, and conversations about our sexual and reproductive health, are considered ‘sexual in nature’ and therefore ‘harmful’ by default.

On the other hand, Tumblr was for awhile seen as one of the mainstream internet’s most open spaces. Late last year, Tumblr came out with new rules which meant that “Posts that contain adult content will no longer be allowed on Tumblr”. ‘Adult content’ once again, includes genitalia and ‘female-presenting nipples’. Tumblr’s new policies were met with outrage from many users, and pushed sex-workers to other platforms.

Sex-workers have frequently raised the problem of structural inequality within social media platforms. Sex-workers are outraged at the ‘verified’ status granted by Twitter to the account of the fictional sex-worker/dominatrix, a marketing tool for the new Netflix show ‘Bonding’ — a blue tick they say is difficult to come by if you’re a real-life sex-worker. Instagram sparked outrage from sex-workers when it censored the hashtag #Stripper and related hashtags, which were being used by sex-workers, dancers and adult entertainers to organize, share work and gain new employment.

And who knows censure better than queers and/or trans folks? The Electronic Frontier Foundation has written in its report about LGBTQ+ communities and the corporate web, “policy restrictions on ‘adult’ content have an outsized impact on LGBTQ+ and other marginalized communities.”[16]

And who knows censure better than queers and/or trans folks?

Clarity Haynes, a queer feminist artist, wrote extensively about the censure of her work and information about her work from multiple platforms including Facebook and Instragram. She wrote, “Whose nipples get censored? The rule is: women’s do, men’s don’t. But there is a spectrum of breasts, just like there is a spectrum of gender. There are infinite possibilities of what breasts can look like, and they can belong to men, women, and nonbinary people”.

Many saw the changes in Tumblr’s policies as a part of a chain of events compelled by the passing of FOSTA/SESTA[17] in the US last year: legislation which explicitly governs online sexual content under the ‘anti-trafficking’ umbrella[18] [19]. And because of the immense concentration of internet governance power in a few US-based corporations, laws passed in the US shape internet activity in most countries.

Increasing corporatization is also cited as a major reason behind the restrictions on ‘adult content’, such as what we have seen with Tumblr (now owned by Verizon). Queer and/or trans folks, kink communities, queer and other sex-workers and adult entertainers, sexual health educators (many are overlapping categories) across the United States are facing profound difficulties staying online amidst a growing trend of queer erasure online.

A luta continua (the struggle continues)

Rosa Luz is a trans activist and YouTuber in Brazil, who quite frankly states, “There are no other options. Once I disclose that I’m transgender, I can’t get any work. For me, my YouTube channel was the last option”. Rosa and queer artists in Brazil are struggling under the foot of an extremely conservative regime led by Bolsanaro (elected last year), but are not willing to give up the spaces they occupy online.

Agents of Ishq is a Mumbai-based project designed to ‘give sex a good name’. Agents of Ishq employ Bollywood-style imagery and symbolism in their courageous and frank takes on desire, sex, consent, queerness and more, in the form of music videos, podcasts and blog posts, shared via YouTube and other social media.

LGBTQ+ activists from Mexico to Bahrain are fighting at the frontlines of the struggle for digital rights, against repressive governments and disingenuous corporations, asserting the political importance of tools and methods such as anonymity and ‘fake profiles’, so that queer and/or trans folks can continue being online.

Around the world, LGBTQ+ activists, queer ‘sex-positive’ feminists, sex-workers, artists and educators are leading the charge against the increasingly complex webs of regulation and censorship of sexuality online, where corporate policies intersect with restrictive state law.

Between the increasing conservatism meted out by right-wing governments and leaders, and the near-complete corporate capture of our governments and our societies, we see interesting shifts in the power structure when it comes to the censorship and regulation of sexuality online and offline; at times, reinforcing the power-bases of some of the more traditional players (such as political leaders and lawmakers), and at other times, giving more control to new players (such as internet corporations). This kind of regulation has to then be placed within the context of ongoing attacks on sexual and reproductive health and rights, including on the rights of those of diverse sexual orientations, gender identities and expressions, and those born with variations in sex characteristics.

We see interesting shifts in the power structure when it comes to the censorship and regulation of sexuality online and offline; at times, reinforcing the power-bases of some of the more traditional players (such as political leaders and lawmakers), and at other times, giving more control to new players (such as internet corporations).

It becomes increasingly important therefore to shift and realign our own focus in some ways — whether in activism and/or research, we have to now hold more than one kind of actor accountable, both independently of each other but also in how they work together. We have to be especially vigilant about attempts to regulate sexual expression because it may be framed in a language different from the language of censorship we are used to. We have to critically interrogate laws and policies, by state and private actors, equally, allegedly meant to ‘protect’. Similarly, we have to sharpen our focus on who is most adversely affected by these attempts to ‘protect’. We have to substantively examine where the harmful effects of censorship are most keenly felt.

The good news is that it is clear that, despite continuing double-standards being used in the service of the censure and regulation of women’s sexualities, queer and non-normative sexualities and sexual expression, many internet users continue to subvert existing frameworks. After all, various forms of sexual expression have survived many centuries and several ‘wars’, ideological and legal. In reality, censorship has never really won, but especially not in its battle against sex.

In reality, censorship has never really won, but especially not in its battle against sex.